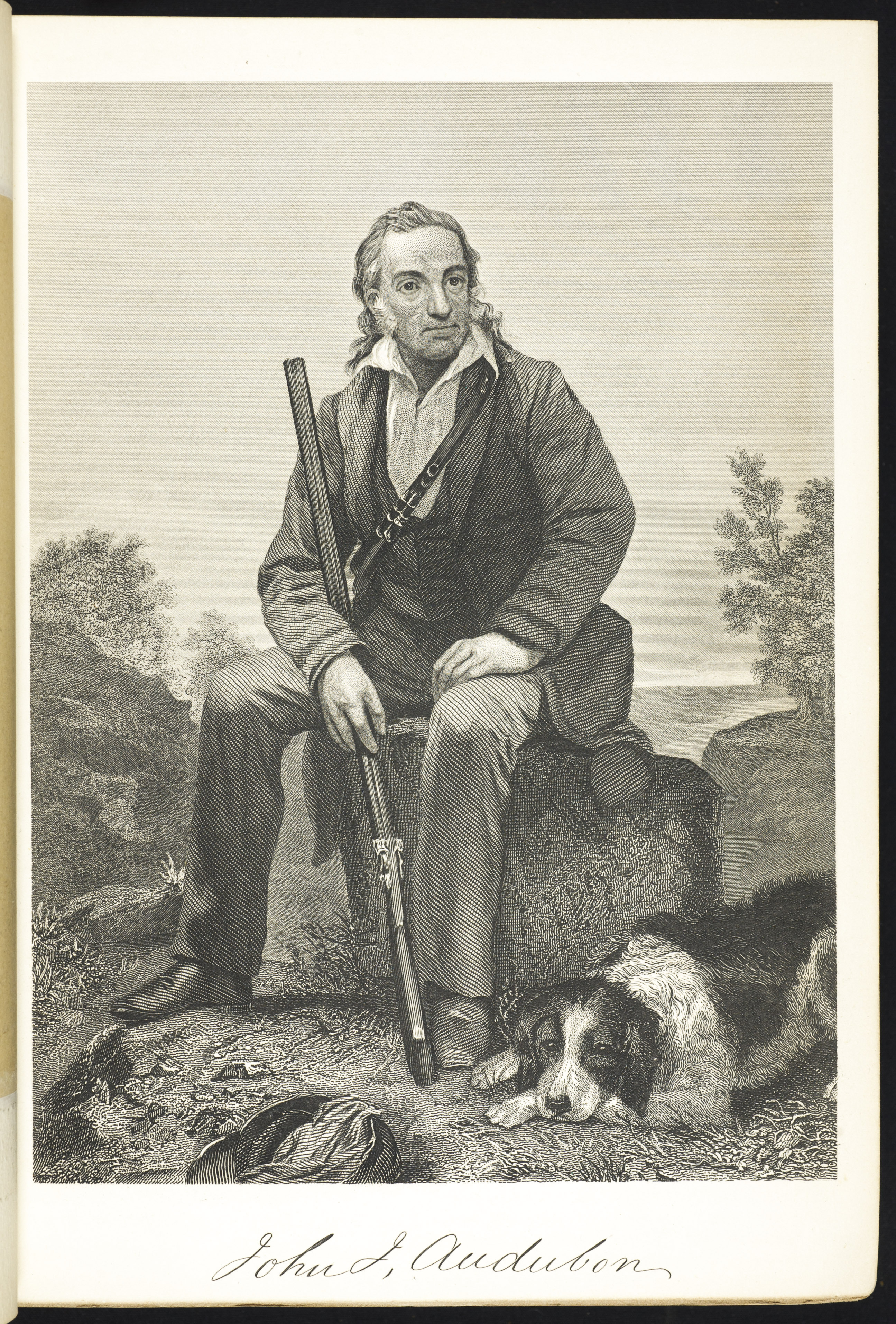

John James Audubon

John James Audubon (1785–1851) was America’s first painter of international stature. His bird paintings not only changed the tradition of natural history illustration, they also had a lasting impact on the development of ornithology and bird conservation. As a nature writer, he deserves to be mentioned in the same breath with Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, Aldo Leopold, and Rachel Carson.

Born in Haiti, as the illegitimate son of a French plantation owner and slave-trader, Audubon grew up in Nantes, where the images of revolutionary violence imprinted themselves on his mind. To avoid being drafted into Napoleon’s army, he left France for the United States in 1803. Living on his father’s estate in Mill Grove, Pennsylvania, Audubon developed a way of rigging up his specimens so that they continued to seem alive even after they had been killed. Audubon’s new method, which shunned the stuffed specimen yet relied on the wired model, required that he finish his drawings “at one sitting” (which would then often take more than an entire day). After trying his hand at a variety of business ventures, among them running a store in Henderson, Kentucky, Audubon set off for New Orleans, the Paris of the South, to get serious about his painterly ambitions. And he did: 80 of the 435 birds that make up Birds of America were painted there. Louisiana galvanized Audubon’s development as an artist. It was here that he began arranging his birds on his sheets in such a manner that his paintings told memorable stories—of survival, death, and the artist’s inextricable involvement with his subjects. Unable to find a printer capable of reproducing his paintings in the format he desired, Audubon left his wife, the Englishwoman Lucy Bakewell, and two young sons, John Woodhouse and Victor Gifford, behind and sought his luck in England, where he eventually formed a lasting partnership with Robert Havell, Jr. and began to sell the finished plates in installments of five at the price of 2 guineas (more than £ 2 in today’s money) to subscribers in England, Scotland, Wales, continental Europe and, increasingly, United States.

With the publication of a pocket–sized edition of his Birds of America, the Royal Octavo, lithographed and hand–colored by the Philadelphia firm of J.T. Bowen from 1840–1844, Audubon, haunted by lifelong worries about his illegitimate birth, rose to fame and wealth. Audubon’s last great work, The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, finished mostly by his sons and his collaborator John Bachman, was still shaped by his vision. Quadrupeds was the outcome of the only trip Audubon undertook to the western United States, where he was shocked by the slaughter of the buffalo he witnessed (although, characteristically, he also took part in it) and pitied the conditions under which Native Americans subsisted. After his return, he gradually succumbed to dementia. A shocked Bachman, visiting Audubon in 1848, found his friend’s mind “all in ruins.”

Audubon’s oversized personality and work have left indelible traces in art, science, and literature, in the United States and beyond. His vivid insights, in his drawings and essays, into the behavior of birds made him one of the most frequently cited sources in Charles Darwin’s books and prepared the way for Peterson’s popular field guides. Writers from Sarah Orne Jewett (“A White Heron”) and Eudora Welty (“A Still Moment”) to Maureen Howard (Big as Life, 2001) have responded to the challenge of his often outrageous persona. In 2002, the Canadian novelist Katherine Govier devoted a novel, Creation (2002), to the collecting trip to Labrador Audubon undertook in 1833, where he grew disenchanted with the killing of birds in which he knew he was complicit, too. “Nature herself seems perishing,” he wrote after watching fishermen kill over four hundred gannets in an hour.